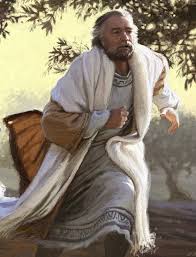

Next to the picture of God’s own Son hanging on the cross and pleading for the forgiveness of His killers, the most poignant scene that would bring tears to the eyes of anyone who truly contemplates the narrative, in my view, is the remarkable run of the heart-broken father towards the returning “prodigal son”.

Let me reproduce my account from my Kabul Diary (I spent 5 months in post-conflict Afghanistan several years ago)

Quote

And on another Sunday – sorry Friday (Friday is the weekly holiday in most Moslem countries), I heard the most wonderful, in-depth, set in the middle eastern context expounding of the story of the Prodigal Son. Let me just give you some highlights. When the younger son asked for his share of the property, it was a death wish on the father, for property divisions do not take place until the father is dying or dead. To the younger son, the father doesn’t exist anymore. He was cutting himself off. Yet the father, unmindful of the enormous shame it cost him in his village, lets the son go. Frightening freedom. And a falling away from the family banquet table.

Then the image of the father pursuing his son. He must have been looking out for him day and night. When he was still a long way off, he runs. He, the village elder, tucking his robes and running. The sort of thing that is never done. Men of honour do not run. But here was the father, running. Do you know why? To prevent the younger son from suffering shame and scorn from the village folk as he enters. The father runs towards those who are lost.

At this point, the younger son is still not repentant. No clue about the reconciliation that is possible. But he is sadly still in a lowly state of filling his stomach even as a hired labour as against permanent staff. In that position, he reckons he wouldn’t have to reconcile with his father. Get the wages, do one’s own thing. Have nothing to do with the father.

But the father would have none of it. Nothing less than the restoration of son-ship and a place at the banquet table. Many in the Moslem world say “fine, the son went astray. The father is merciful. He forgave him. Where is the need for the cross?” little understanding the enormous price the father paid, the guilt and the shame he took upon himself in doing the work of redemption. Oh, the story is really about a prodigal father; a father who is so generous, so recklessly abundant in his love.

Unquote

Cut to Onesimus

(as recorded in Wikipedia with extensive modifications based on Chris Kempling’s commentary on the subject, quite a lot of it verbatim)

“Onesimus of Byzantium was probably a slave to Philemon of Colossae, a man of Christian faith.

The name “Onesimus” appears in two New Testament epistles—in Colossians 4 and in Philemon. In Colossians 4:9, a person of this name is identified as a Christian accompanying Tychicus to visit the Christians in Colossae; nothing else is stated about him in this context.

The Epistle to Philemon was written by Paul the Apostle to Philemon concerning a person believed to be a runaway slave named Onesimus. Onesimus found his way to the site of Paul’s imprisonment (most probably Rome ) to escape punishment for a theft of which he was accused.

As stated, Onesimus was a runaway. Although the reason is not made specific, the text implies that Onesimus had stolen a substantial amount of money, and probably used some of it to buy passage to Rome. A likely scenario is that Onesimus was remiss in his duties and was criticized for laziness or shoddy work by Philemon before his skedaddle. Rather than reform his behaviour, he decides to relieve his master of a sum of money and flee to the big city.

While in Rome, he meets Paul who is imprisoned there. Onesimus undergoes a conversion experience after his meeting with Paul and becomes extremely useful to him. And later Paul writes a one-page letter to Philemon. The reason for Paul’s letter is a plea for forgiveness on behalf of Philemon’s slave, Onesimus.

Paul uses a play on words to emphasize Onesimus’ new status. Onesimus means “useful” in Greek, but of course, he became worse than useless when he stole his master’s money and fled to Rome.

Paul writes, “Formerly he was useless to you, but now he has become useful both to you and to me.”(Phil. v.11)

There is an additional play on words in the original Greek. The specific Greek word for useless is “achrestos”, which is very close to Christos (Christ).

In other words, previously Onesimus was “without Christ,” but now he is “euchrestos”, i.e. “full of Christ”. This type of word play is common in rabbinic writing, of which Paul was a master.

Under Roman law, a slave owner had complete authority over those he owned. If he chose a severe discipline, up to and including death, that was within his right. So it is no small matter for Paul to return Onesimus to Philemon.

(I wish to acknowledge the immediately preceding paragraphs are mostly a verbatim reproduction of Kempling’s commentary. I saw no reason to write something of my own when Kempling has done such a wonderful job)

It is interesting to note how Paul makes it difficult, nay impossible for Philemon to reject his plea, by joining argument to argument in a masterful manner. Initially the letter begins fairly ordinarily with greetings and thanksgivings but suddenly shifts gear when Onesimus is brought into the picture. Almost like the tightening grip of a python, Paul refers to him as his son, himself as an old man and a prisoner – sentiments that cannot fail to evoke sympathetic consideration of his request. Philemon was wronged by Onesimus and was probably quite angry with him for his dishonesty and theft. And here Paul was dealing blow after blow in an effort to thaw his vehement zeal and gradually melt him down.

And the coup de grace comes when Paul somewhat facetiously states “If he has done you any wrong or owes you anything, charge it to me. 19 I, Paul, am writing this with my own hand. I will pay it back—not to mention that you owe me your very self. “

eh?

And then the pièces de ré·sis·tance.

I do wish, brother, that I may have some benefit from you in the Lord; refresh my heart in Christ. 21 Confident of your obedience, I write to you, knowing that you will do even more than I ask.

6 – 0, 6 – 0, 6 – 0

game, set and match to Paul!

Whence his confidence?

If we read the letter closely, I think we can see “the love of Christ that constraineth him (2 cor. 5:14), the ministry of the Holy Spirit that emboldens him and the grace of God that energizes him.

Unlike the other Pauline epistles (Kempling notes), which are letters written to a general audience of believers in a specific church, Philemon is personal, written to one individual. One wonders why it became part of the canon of scripture, given its uniqueness. There are several important themes at play in this letter. The most obvious is the theme of forgiveness.

Ah…. forgiveness!

C.S. Lewis once said, “Everyone says that forgiveness is a wonderful idea until he has something to forgive.”

And everyone knows a story (I do) in their family when lack of a forgiving spirit resulted in lifelong animosity. As a matter of fact, I come from a region of Tamil Nadu where they make a fetish of their unforgiving spirit.

In some parts of the country, they wear it as a badge of honour and even do not hesitate to kill one another to uphold it.

I think the number of couples congregating in family courts seeking divorce can go down considerably if they personalize for themselves the letter to Philemon.

(But it is not my case that all the marriages can be saved or all the problems of the world solved if we practice forgiveness. Admittedly there are other intractable issues. But we will not address them here).

Yes, forgiveness is a rare quality.

Have you tried it?

Right through the Bible, we find instances of forgiveness that blows our mind.

Let’s start with Genesis. A most unpleasant scene in Pharoah’s court was avoided when Joseph uttered these words to his brothers: “ But as for you, you meant evil against me; but God meant it for good, in order to bring it about as it is this day, to save many people (Gen. 50:20)

Esau had every reason to harbour resentment and anger against his brother Jacob. Jacob knew this only too well and was practically shivering in his pants when the time came for them to meet. Yet see how Esau encounters his brother: “But Esau ran to meet Jacob and embraced him; he threw his arms around his neck and kissed him. And they wept” (Gen.33:4)

And the Lord turned the captivity of Job when he prayed for his friends (Job 42: 10). And who are those friends? Eliphaz the Temanite, Bildad the Shuhite and Zophar the Naamathite started with sympathy for Job’s pathetic condition but quickly moved to argue that this was all the result of his sin against the Holy One.

We can now examine another aspect of forgiveness.

Is it sought? Did anybody say “sorry, please forgive”?

Joseph’s brothers surely waffled around and Jacob parted with some of his (doubtfully?) gotten gains in supplication.

In the case of Onesimus, he probably was not in a position to say anything to Philemon directly, since the relationship was slave-master; Paul had to do all the pleading.

But it doesn’t happen in all cases and yet we are called to forgive. Onesimus himself could be a case in point. He himself did not ask but yet Philemon was obliged because he was a Christian.

So what if he was a Christian?

We have to go to Eph. 4:32 for the answer “And be ye kind one to another, tenderhearted, forgiving one another, even as God for Christ’s sake hath forgiven you. “ and 1 John 3:16 Hereby perceive we the love of God, because he laid down his life for us” ….yes, on the cross as atonement for our sin.

And what happens if you do not forgive?

Good question

Advice columnist Ann Landers once wrote, “Resentment is like allowing someone to live rent-free inside your head.”

Mentioning this Kempling writes, that forgiveness is essential for the restoration of a right relationship between two people. Failing to forgive, and hanging on to resentment, can become emotional cancer. So Forgiveness is not for the other person — it’s for you.

This of course is true for all people, Christian and non-Christian.

Mahatma Gandhi endeavoured to practise principles arising from Christ’s Sermon on the Mount in his dealings with the British colonial masters.

In our own times, we have seen Nelson Mandela emerge emotionally unscathed from 27 years of prison under an apartheid regime and go on to become President of South Africa.

The Gandhi family stated that they harboured no resentment against the killers of Rajiv Gandhi.

Gladys Steins went on record that she forgave Dhara Singh accused of the heinous murder of her husband and two young sons.

Bravo!

That said, forgiveness is basically a divine quality that Christians are called upon to demonstrate.

And why?

For “God for Christ’s sake hath forgiven you.”

Indeed, that was Christ’s mission in coming into the world. Yes “This is a faithful saying, and worthy of all acceptance, that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners ( 1 Tim. 1:15, KJV)

And forgiveness is not easy, as we have already observed.

And it is costly.

Human forgiveness may cost one in terms of money, perceived prestige and honour, an opportunity to exact revenge and satisfy one’s offended ego and so on.

But divine forgiveness?

“And when I think that God, His Son not sparing

Sent Him to die, I scarce can take it in

That on the cross, my burden gladly bearing

He bled and died to take away my sin”: Stuart Hine

Yes, it cost God the life of His only Son. John 3:16 makes it clear: “ For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.”

Let’s examine further. Okay, Jesus died on the cross as an atonement for the sins of the whole world.

But is the whole world forgiven?

The answer of course is a resounding NO because everyone has not accepted it.

Yes, it remains for us to personally appropriate the sacrifice of Christ on the cross, that is “believe”. It is a simple act that costs us nothing but our sense of control over our own destiny, the need to self-flagellate, contribute money (sometimes our hair), undertake penance and visit a hundred deities around the country, come in the way.

Paul goes even further.

So if you consider me a partner, welcome him (Onesimus) as you would welcome me. (v.17)

What? Onesimus – a slave, a thief and a runaway, is now to be treated as a brother in Christ.

Preposterous!

So, the most important underlying theme of Philemon is the brotherhood of all believers (writes Kempling).

He goes on: Christianity is a faith which erases ethnicity, social distinctions, employment status, etc. All are equal in Christ and must be treated as brothers and sisters. This would mean that caste distinction has no place in Christianity.

Swallow that!

It is also profitable to take a look at the Lord’s Prayer.

……“and forgive us our trespasses” (Matt. 6:12)…….

It is interesting that we can set the degree to which we want forgiveness from God, for this ends with the phrase “ as we forgive those who trespass against us”. The onus then is on us! There is little point in importuning God with our feverish and pathetic pleas for forgiveness when He has already given the handle in our hand!

To many, this is not easy. They have lovingly nurtured feelings of hurt and grudge so long that the very idea of ‘letting go” is anathema to them.

The Bible enjoins us to

“Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world.” (John 1:29)

“Have you been to Jesus for the cleansing pow’r?

Are you washed in the blood of the Lamb?

Are you fully trusting in His grace this hour?

Are you washed in the blood of the Lamb?”: – Elisha Albright Hoffman

Are you forgiven?

________________________________________________

What a message on the first word from the cross.Nothing less than a mini research paper.God bless your ministry.

Thanks Sujatha